I give this work to the blessed Mother to set before our Lord.

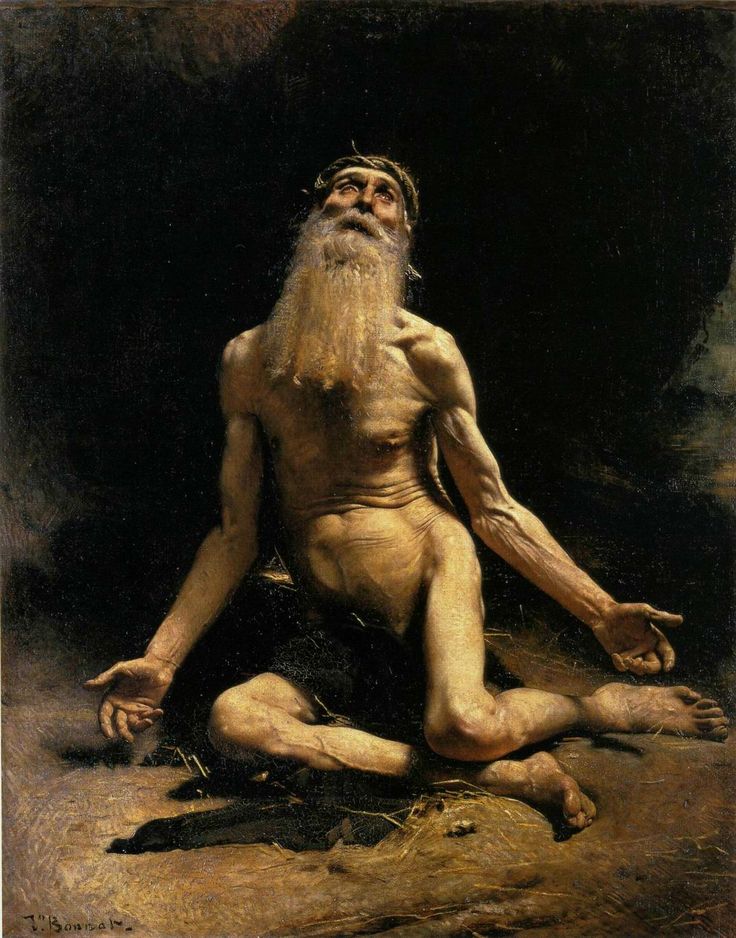

Job 1:21 “the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Info: Princess Mononoke is a 1997 movie by Studio Ghibli, which was released in the US in 1999. It takes place in Japan sometime in the Muromachi period.

Spoilers: If you haven’t seen it go watch it, and perhaps even read this before watching it so you can judge if I’m accurate or off my rocker.

Also, just a heads up, this is one of Ghibli’s more violent films with some warrior’s getting their arms cut off, etc. Just be aware of that before you unreservedly show it to little kids thinking it’s Totoro part II.

Why is it so good?

Because Miyazaki isn’t making the argument “nature = good; industry = bad.” Instead, I suggest he’s showing us what it means for human society to have a proper relationship with divinity. His microcosm for this is Ashitaka, who is then juxtaposed with people like Lady Eboshi, and San. The wisdom in having Ashitaka as an outsider is that he gets to be a tertium quid that both sides think is “our guy.” The result is that at the end of the movie we aren’t left with a pithy black and white lesson like “mankind will never outlast or out do nature” but rather the uneasiness that while there are indeed forces greater than mankind at work, mankind will still continue to work – for better or worse.

First theme: Divine Providence

Although perhaps that last theme to be grasped while watching the movie, I want to start with the theme of Divine Providence. This theme comes to the forefront when the Boar clan, led by old boar Okkoto, comes to the forest to declare their attack on Iron Town and meets our MC Ahistaka. When the boars are told how Ashitaka was attacked by the previous boar guardian Nago, who had turned into a demon, they don’t believe him at first. Especially when they hear that the forest spirit healed Ashitaka’s bullet wound but did nothing – and does nothing for the forest in its time of need.

We see here the problem that has plagued countless hearts from the dawn of time: If there is a being who is allegedly all-powerful and respected as morally good and protecting all things, then why doesn’t he/she/it act in our time of need? Any character in Princess Mononoke could ask such questions: Why would the young and strong Nago be corrupted into a demon, why would such an old boar like Okkoto remain for such a big battle? Why would the forest spirit heal Ashitaka’s bullet wound but not his cursed arm? Why did the forest spirit kill Okkoto rather than heal him and Moro who were dying? If the forest spirit was close to wiping out Iron Town when searching for his head, why didn’t he wipe it out before Eboshi killed him? And the list could go on and on.

Keep in mind, however, that Miyazaki has no intention of portraying a Christian world and so comparisons I make will be stretched a little. With that in mind, perhaps we can still see Miyazaki wrestling with the idea that God can bring a greater good out of any suffering. The happy circumstances at the end of the film only come about because of Ashitaka’s curse, Okkoto’s rage, San’s rebellion, Eboshi’s attempted deicide, and Iron Town’s environmental exploitation. Not everything is as everyone would want it. We see this in Eboshi rebulding, and San continuing to live in the forest. Yet there seems to be a sense that maybe everything is indeed as the forest spirit wants it. Much could be said about this, but we’ll stop here for now.

Second theme: being nice =/= being good

Our second theme is displayed in Lady Eboshi’s character. We are introduced to her not as the dictator of Iron Town, but rather its beloved matriarch. She buys out the brothel girls’ contracts and gives them honest work in the iron factory. She employs lepers who would have otherwise been left destitute. She wants the women of the town to be able to defend themselves. In all respects it seems she’s a selfless woman. It seems, but sadly it’s not the case. The subtlety is that all this is done to further her own plans. Make no mistake. I fully support her intention of getting women out of the brothel and giving the lepers honest work. But her prior intention seems to be that all these people are meant to work for her and that there is nothing, no higher power, no higher authority, beyond Lady Eboshi. We see this clearly in her understanding of the spiritual and sacred when she proclaims “I’m going to show you how to kill a god, the trick is not to fear him.” The ignorance – as if spiritual creatures could “die” – comes from her lack of piety or fear of the Lord, which, as we know “is the beginning of wisdom” (Pro 9:10).

Ashitaka on the other hand is shown not only to respect the spiritual world, but is also aware of the role the spiritual plays within the material. He knows where humans should be in the grand scheme of things. This is why he can prioritize the lives of Iron Town’s people in battle, but also tries to dissuade them from advancing any further. As I mentioned before, we see the other extreme in San’s character. San identifies so much with the forest spirits that she almost rejects being human. There’s a moment when she tries to kill Ashitaka and while holding her back he says “you’re beautiful.” We might say it’s the affirmation of her humanity – in contrast to her demonization by the townspeople – that starts to change San’s way of thinking.

Honorable Mentions (aka but wait – there’s more!)

There is always more to say, but I’ll leave you with four extra foods for thought.

- The West

- At the beginning we hear from Ashitaka’s village that the west is where bad things come from e.g. the boar demon. But the west is also the place of the forest spirit. It’s interesting that in order to be healed, to reach the place of the gods, one also needs to go through adversity.

- Death

- Moro, aka “Mother Wolf,” claims that Nago (demon boar) was corrupted because he feared death. Moro herself has been injured by an iron slug but isn’t corrupted precisely because she doesn’t fear death.

- Marriage

- When Moro tells San about Ashitaka’s proposal she says “he would share his life with you.” A short line that cuts to the heart of marriage. And we can see why San – who has never lived with other humans – would be afraid of such a thing.

- Anger -> Stupidity

- Moro tells San the humans are purposefully enraging the Boar clan so that in their anger they will become stupid. Sadly, it works. We’re reminded here that to be patience – which is the opposite of angry – is to suffer.

Much more could be said, but for now let’s spend some time appreciating the invisible realities around us.

St. Justin Marytr, pray for us!

Leave a reply to COLORLESS: Christ and History – Anime Christi Cancel reply